In recent times, I've found myself speculating quite a bit about the nature of my ancient home, and what it might have to say about the building practices of housewrights in the early New Haven Colony.

But now, some of these considerations actually have me questioning the exact age of the Hawkins house. My home is often claimed to have been built sometime between 1670 and 1675. The local land records say 1670. The Hawkins family genealogy says 1675, but I have found no particular justification for this date in their account. We do know, via the old town records, that the land on which Joseph Hawkins built his home was granted in June of 1670. We also know with certainty that the current day house was sold by the Hawkins family to the Gaynor family in 1853.

The Old Hawkins House, probably around mid-nineteenth century. And we also have it on the word of Samuel Orcutt and Ambrose Beardsley, in

The History of the Old Town of Derby, Connecticut, 1642-1880 (published in 1880) that Joseph Hawkins "...built a house where now the old Hawkins house stands, on Hawkins street, where he died in 1682" (p. 726). I'd previously taken this as confirmation that my home was constructed before 1682, and that Orcutt and Beardsley were asserting that the "old Hawkins house" was, more likely than not, the original home, albeit without having any definitive proof.

However, in re-reading this passage, I now think that Orcutt and Beardsley may have had their suspicions that the house on Hawkins street was built in more recent times, and their comment "where he died in 1682" was probably a reference to an earlier home (or perhaps just the Hawkins street location, generally), and not necessarily the current day house. But why would they have reached such a conclusion?

The Reverend Richard Mansfield house, c. 1700, Ansonia, Connecticut. A pristine example of a Second Period Connecticut saltbox.A classic text, nearly as old as Orcutt's and Beardsley's history, is Norman Isham's and Albert Brown's

Early Connecticut Houses, originally published by Preston and Rounds in 1900, and then republished by Dover in 1965. In it, Isham and Brown surveyed 29 ancient Connecticut homes, some of the earliest of which no longer survive today, and attempted to describe the general characteristics of homes built during the three major periods of Connecticut colonization.

There are many aspects of the current day Hawkins house's architecture and construction that suggest it's more a product of what Isham and Brown had defined as

The Third Period of the New Haven Colony, roughly from 1700 to 1750.

First of all, the Hawkins house is simply too big to be a First Period (1638-1675) home, according to Isham's and Brown's characterizations. Homes of the First Period generally consisted of two rooms, Hall and Parlor, separated by the chimney bay, with the entrance and second floor stair in front of the chimney column. Although the front section of the Hawkins house is indeed configured in this manner, the house also has a rear section of nearly equal area encompassing both the first and second floors, defining a large kitchen on the 1st floor, and work rooms and additional bed chambers on the second floor. All this without the lean-to extension typical of Second Period (1675-1700) saltboxes. The Hawkins house plan, therefore, is consistent with the design of a Third Period home.

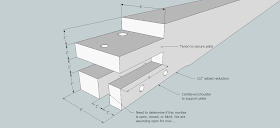

The beefy central attic joist in the Hawkins house holds the midsections of adjacent end-bay tie-beams together, using a half dovetailed joint at each end. The vertical boards fastened to the left side of the joist create a partition wall that divides the front section (hall and parlor) of the house from the rear section (kitchen area). Second floor and attic joists run longitudinally, and there are no summer beams, except under the first floor. Also missing from the Hawkins house are the massive summer beams found in most First Period homes, which, in Connecticut, typically spanned the two end bays from the chimney girt to a cambered wall girt at each end, respectively, defining the joist system of the 2nd floor. Instead, Hawkin's house joists in the end bays run longitudinally from chimney girt to wall girt on the 2nd floor, and likewise from tie-beam to tie-beam under the attic floor. The only summer beams are found in the first floor system, visible from the cellar.

The Hawkins house also has a 10" roof pitch, in contrast to the much steeper pitches used by First Period New Haven Colony carpenters, according to Isham and Brown. The roof system does, however, include collar ties, something often missing from later period New Haven Colony homes.

These points really hit home for me while attending the Timber Framers Guild's TTRAG Symposium 2011, last week in Danvers, and Topsfield, Massachusetts. Jack Sobon mentioned to me that, in addition to its basic plan and size, many of the apparent framing simplifications exhibited by my house were typical of later period homes. Several others mentioned that the lack of bracing in favor of heavy sheathing, and the absense of traditional English tying joints in the post/tie-beam/plate connections, also seemed indicative of a later period home. Jack suggested conducting a dendrochronological survey of the frame, to attempt to verify the true age of the house. Thanks to a rather large, accumulated database of wood core samples, modern dendrochronological dating can be extremely accurate, sometimes as close as one year. So, as you can imagine, this is now a part of my survey plans.

Where post, tie-beam, and plate all come together, a relatively simple tying joint is used in the Hawkins house frame. (The Mansfield house in nearby Ansonia uses an almost identical joint). On the other hand, my Guild colleagues also showed considerable interest in the design of the simplified tying joint used in the Hawkins house frame, whose internal geometry I have yet to completely determine. Both the Hawkins house and nearby Rev. Richard Mansfield house appear to share this joint. Several attendees professed being unfamiliar with this particular style of joint, and concluded that I might've come across a New Haven Colony vernacular design that was worthy of further investigation. So, of course, I plan to continue with that, as well.

Is it possible that the current Hawkins house is a latter day extension of an earlier home built by Joseph Hawkins? That's certainly possible, but I have yet to find any hard evidence of a conversion. I think it more likely that some descendant of the early Hawkins family decided to build a new home, either on, or near, the site of the original home. If that's true, what happened to the original home is anyone's guess.